For a Worker’s Recovery Plan - The Causes and Cures of a New Great Depression

Eric Lerner

Economics is now not just for the experts. If anything is clear from the panic that started in mid- September, 2008, it is that workers must understand the economy. For clearly the “experts” have no idea what they are doing. The leading economic minds have put forward new bailout plans and rescue plans on a nearly daily basis, but the markets have swirled down a bottomless drain. They have thrown their “free market” ideology overboard like so much excess ballast. Despite their best efforts, mass layoffs are spreading from the US to China, steel plants are shutting down because commodity prices are falling too low for profitable operation, privatized pension funds are evaporating, housing is becoming impossible to buy or sell, government budgets are being slashed. So it is up to us to understand what is going on and what can be done about it.

For this crisis, grave as it is, opens up the possibility of radical change. If someone is poisoning you, you may die before you even know you are under attack, but if someone comes at you with a battleaxe you have a better chance of taking action and fighting back. The working class has been suffering large losses in living standards for three decades but these gradual losses have been like slow poison, never triggering massive resistance from workers. This crisis has shown workers that someone is coming at them with a battleaxe and they want to fight back. Around the world, workers are united in anger at the spectacle of governments funneling trillions of dollars—taxed from workers—to rescue the richest of the rich. The bailouts have raised in concentrated form the question—what should the government do about the economy? The capitalist system has spectacularly failed and workers are fighting against paying for the cost of that failure.

But to fight back, we must know what we are fighting for. The working class must arrive at its own solution to the crisis. Coming together, from many different movements—immigrant rights, labor, anti- war, civil rights—and from every region, eventually form all across the world, we have to arrive at a global Workers Recovery Plan that we all can unite around. To do this will take organizing and effort, conferences and discussion at all levels.

The key question is what must be done to end the crisis—what is the cure to the economic sickness that has gripped the world? To find a cure, we must know the cause. We must answer some basic questions: How serious is this crisis—is a new Great Depression, like that of the 1930’s beginning? What caused that Depression and is this a similar situation—what has caused this crisis? Will any of the rescue plans work? How do we judge what economic theories or ideas are right? And most important of all, what actions can protect the working class, can create rather than destroy jobs, raise rather than lower wages and standard of living, end the crisis and move society forward? For above all we have to remember that this crisis is not some act of nature that must be endured like an earthquake. The factories are still standing and can produce just as much today as in 2007; the workforce is still able to do the same work. No physical destruction has yet taken place so there is no physical reason why workers living standards must go down.

Symptoms

To judge how to cure an illness, we have to start with the symptoms. Is the problem a high fever, or a bleeding wound? In the case of the global economy the symptoms that everyone talks about is overvalued assets—financial assets that somebody thought were worth a lot more than they now are. In the story that the media is telling, this is basically about mortgage loans made over the last few years on houses that are now worth much less than the lenders thought they were. Somehow, these loans are all going bad now, causing some banks losses, and making all banks scared to lend to each other. In this story, it is a limited, short-term problem and the patients, the banks, really only need some nice-tasting medicine—in the form of a couple of trillion dollars poured into them —so that they will feel safe enough to lend again.

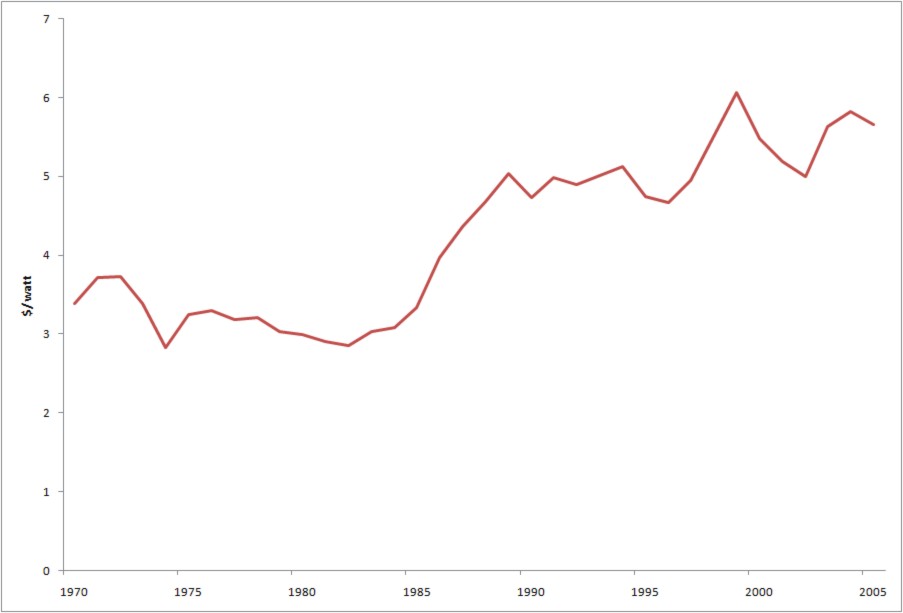

This story contains some truth, but just a bit. It is true that a big part of the problem is vastly overvalued assets—things that have value only in the minds of capitalists—what is called “fictitious capital”. But the symptoms started showing up twenty years ago, not just a few, and the scale of the problem is many times bigger than the US housing market and affects many other types of capital. To see how much of capital is fictitious we can use a couple of measures. First we can compare the total amount of world capital—the sum or stocks all bonds, all loans—and compare it to real production, just as we can judge the scale of the housing bubble by looking at total value of housing divided by the number of houses. If we divide total capital, in constant, non-inflated dollars by, say, the total production of energy in the world (figure 1.) we see that it was pretty constant until 1985, rose hugely in the late ‘80’s , again in the late 90’s and again in the last few years. If we judge from this measure almost half of all capital is fictitious.

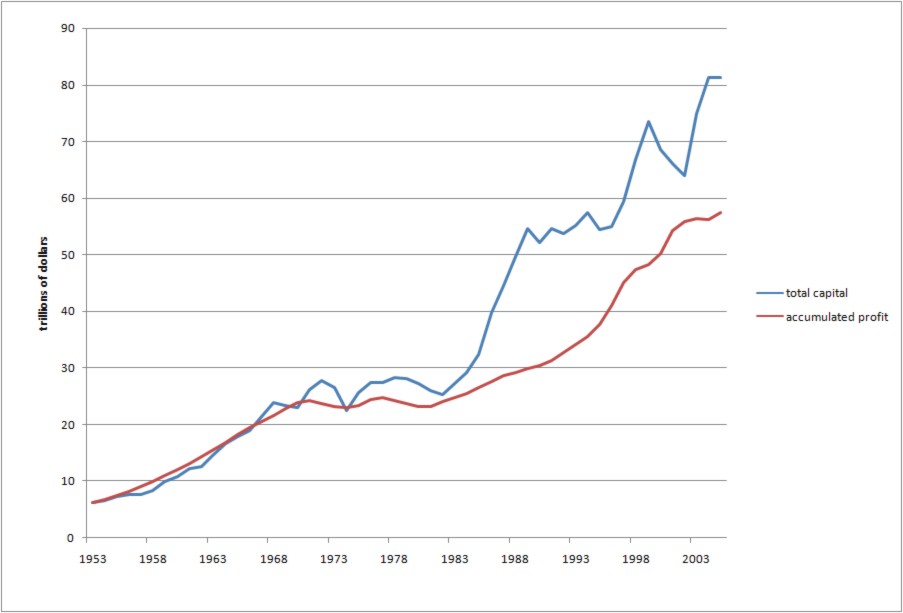

But let’s measure capital the way capitalists do—as accumulated profit, the sum of all the profits made over all the years. We can take the amount of profit reported by the capitalists each year and add them together, after subtracting inflation. That total, by capitalist accounting, should equal their current capital—the sum of all profits. In figure 2, we plot the market valuation of capital (upper line) and the accumulated profit, (lower line) both in constant dollars. Again, a huge gap starts to open up in the mid-80’s. By this measure things look somewhat better —“only” 30 % of all capital is fictitious. Since all capital, at the end of 2006, amounted to almost $80 trillion, the fictitious capital—the bubble—amounts to somewhere between $25 and $40 trillion.

To give some idea of the scale of these numbers, the current (Oct. 13) value of all stock on all the world stock markets is about 15 trillion. Total losses on the markets since the peak in 2007 are already around 10 trillion. The total net worth of all world banks (assets minus liabilities) is about 2 trillion dollars. So if all this fictitious capital is wiped out it would wipe out all the value of all the world’s stock markets and bankrupt every bank in the world. So you can see why capitalists might be a bit worried. This is not an irrational panic. This is the total bankruptcy of the entire financial system. If all these assets—mortgage, curate loans, credit card loans and the strange bets they call derivatives, are marked down to what they are worth by capitalist accounting, all the banks are bust and the shares are worthless.

It is not the existence of the fictitious capital that has caused the panic—after all, that has been around for 20 years. It is the process of deflating the value of that capital that is the panic. Once a critical mass of capitalists begins to sell assets in fear that others will do so, a panic builds on itself, since the wiping out of assets causes—or rather reveals— insolvency, which forces capitalists to raise more money by selling more assets, which forces prices down further. And since this fictitious capital has been so widespread, all assets are overvalued and all—stocks, bonds, commodities like oil and steel –are being sold off and their prices are collapsing.

So we can see that even the two trillion dollars being tossed to the banks in the latest global bail-out plan is a mere drop in the bucket compared to the huge scale of this problem, which goes way beyond just the US housing market to every type of financial asset. And investors cannot be “reassured” because the system really is bankrupt.

By now, the symptoms have spread well beyond the financial sector. In the past months, steel production has dropped by 20-30% in most countries, auto sales have dropped by a similar amount, and more than a million workers have lost their jobs.

Diagnosis

Yet, does this really mean that this financial panic will, as in ’29, set off a Depression, with unemployment rates of 20% or more, ever-falling production, and falling wages? We have had bursting bubbles and financial panics before—such as the dot.com bust at the beginning of the decade, which led to relatively little damage in the real economy of production and jobs. Is a Depression a real threat? What caused the Depression of the 30’s and are similar processes operating today?

Here we have to turn from looking at the symptoms of the disease to diagnosing its causes. To understand what is wrong with the economy we have to know how it works, just as to diagnose an infection we have to know how the body works. But how do we judge if an economic theory is right, if we have the correct diagnosis? We can see that the “free maker” theory of neoliberals, with all its fancy mathematical models of valuation and baloney about the wisdom of the markets was wrong, just by seeing the results. But how do we know about other economic—or is this whole thing just too complex for ordinary mortals to understand?

We basically have to use the same scientific method that has served so well in finding about other aspects of reality. The economic behavior of society can be studied as can the infectious behavior of bacteria using similar methods. A scientific theory is judged to be useful and valid if it can, with relatively few simple and understandable concepts, quantitatively predict real phenomena. It has to be relatively simple to be useful—if a theory needs a new explanation for every new thing observed it is not a very useful theory. But if one can take from a few examples a rule that is proved true again and again in the past, then we can have some confidence it will be true in the future as well.

So, when a doctor is diagnosing a disease, based on certain symptoms, he or she will order tests to confirm the diagnoses, predicting from the diagnosis what those tests will show. If the diagnosis correctly predicts all the tests with one hypothesis—you have the pneumonia—then the diagnosis is a good one. But if for each test a new and surprising result is found, the doctor rejects the diagnosis and tries to find a new one that fits all the facts.

So let us see if there is a relatively simple, coherent explanation of what is wrong with the economy the basic cause of the crisis, that we can test against the evidence of economic history. If it seems correct, then we can use it to predict the course of the crisis and to outline a possible cure.

What is our diagnosis? The underlying cause of the crisis is that global capitalism has run out of new external markets—there are no more Chinas out there. Capitalism cannot sustain itself, and never has, just by selling products to an “internal” market of capitalists and the workers that they employ. It has always required an ever-expanding external market—consisting of peasants—small farmers—and other non-capitalist producers. When there are no more new external markets to expand into, as at present, capitalism faces a huge crisis and begins to consume the society it has built.

This diagnosis is not something new or original. It is based on work done a century ago by the German revolutionary socialist Rosa Luxemburg. So it is possible to look at this theory, see if it makes sense, and see if it works to explain what happened in the Depression and what is happening today, comparing the predictions that Luxemburg made right before World War I with later events. In this way, we can test is this diagnosis is a valid one, or if we need to seek elsewhere.

Why does capitalism need a growing external market, and why does it suffocate without this? To understand this we have to look at the basic way that capitalism functions. The whole point of capitalism is to make a profit, of course, to sell things for more than it costs to make them. The profit then is accumulated as new capital, reinvested to make more profit. This accumulation of capital, hand in hand with the expansion of profit, is the essence of capitalism.

It is in the basic nature of capital to require not just a profit, but an ever-growing profit. The value of capital to a capitalist is only in how much profit it can make. So growing capital requires growing profit. If a capitalist has a billion dollars and in one year makes a profit of 100 million dollars, at the end of the year he has 1.1 billion dollars and has made a profit of 10%. He then reinvests the $1.1 billion dollars. If he then earns 110 million dollars, he again has made a profit of 10%, with his new capital making 10 million in additional profit. So a profit rate of 10% is equivalent to a growth in profit and in capital of 10% per year. The capitalist is happy.

But if the capitalist only makes the same profit in the second year of 100 million, then the profit of the first years has done him no good—it has not increased his profit and thus it has no value as capital. In the long run, making a constant amount of profit is the same as making no profit at all—the value of capital does not increase, since its only value is to make a profit. Thus capitalism needs an ever-increasing mass of profit to accumulate capital.

But how can that miracle of ever-growing profit occur? If we look at a single capitalist corporation, things seems very complicated, since whether or not an individual corporation can make a profit seems to depend on many things,—the demand for goods, the capitalists’ efficiency in marketing them, how much wages the workers get, their productivity, etc. But, as Luxemburg wrote, we can simplify matters by considering the capital system as a whole, by looking at all capitalists as if they were a single global capitalist corporation. Then we can more easily ask, how can all capitalists, this one global capitalist corporation, make a profit? In this way we can see that if the world consisted only of this global corporation and its workers, a profit would be simply impossible.

To see why this is true, let us imagine that all the goods produced by the economy in a year as piled up in one place. One pile consists of all the goods (and essential services like education and sanitation, if we could pile them up!) that are needed to support the workers at the same standard of living and population as at the start of the year. A second pile is all the goods needed to maintain the “means of production” for a year—all the raw materials, all the replacements for worn-out machinery—and the necessary services like transporting goods that go with all that. But workers are able to produce more goods than are needed to simply sustain themselves and the same level of production. So, they produce a third pile---- a surplus of goods, both means of production and means of consumption that can go into expanding production, building new plants, hiring more workers, increasing wages.

To produce all these goods and services the global corporation has of course had to lay out money—wages to the workers who produced all this. It needs to sell everything to make that money back and to realize a profit. It has no trouble selling the consumption goods to the workers, in return for the wages it has paid them. It sells “to itself” the means of production that replace the ones used up in production. So far the corporation is breaking even. To make a profit it must sell the surplus. But who can buy this surplus?

It can’t be the workers. They get their only income from the capitalist corporation. If the capitalist corporation raises wages so that they can buy the surplus (strange idea!) then there will be no profit, because higher wages will eat it up. If the corporation lends to the workers to allow them to buy more than their wages (which surely does happen) there are strict limits to this process that have become all too obvious recently. The workers have no productive assets they can use to pay off the loans—only consumption goods like homes.

It can’t be the global capitalist corporation. Capitalists can’t make a profit by selling to themselves. We could abandon our assumption of single global corporation, and say that one group of capitalists will accumulate at the expense of another, but capitalists as a whole can’t make a profit this way (nor will any group of capitalists willingly volunteer to dis-accumulate or lose money!).

So who can be the buyer of the surplus? Fortunately for capitalism, the majority of the world’s population has always been neither workers nor capitalists but peasants. It is non-capitalist producers who can and do buy the surplus and enable capitalist accumulation to function. They have all the requirements needed for the process to work. Unlike capitalists, peasants do not accumulate capital. A peasant or small farmer may in good times make enough to feed themselves but they do not as a group make profits that they can then invest. But unlike workers, they can dis-accumulate initially, as capital first penetrates non-capitalist areas. Dis-accumulation is the process of spending (voluntarily or involuntarily) previously-accumulated real wealth to buy capitalist goods. The non-capitalist producers—peasants and non-capitalist societies have wealth to give up that workers don’t have. This wealth, not created or supplied by capitalism creates the critical new demand for increased surplus, thus allowing the production of surplus to expand. Capitalism absorbed the previously-accumulated wealth of other societies — of feudal Europe, of India, of China, vast countries that had for centuries settled affairs in gold and money. Second, when this source was exhausted, capital can loan money to these peasants and their governments — with the collateral being their land and the mineral wealth beneath it. As peasant families, or entire nations burdened with debt default on such loans, capital forecloses, seizing in the process vast real wealth, vast means of producing new wealth.

For capitalism to expand, its surplus or profit must also expand, and since the surplus can only be realized by exchanging with non-capitalist, non-accumulating producers capitalism must continually expand the number of these producers that it trades with. Historically it did this first by destroying feudal societies in Europe, integrating the peasants into capitalist trade, then through imperialism, breaking down barriers, setting up peasants and small farmers where none existed before, forcing trade on unwilling partners, conquering the entire world. In the process, it not only achieved the expanding external market it had to have, it grabbed the natural resources its expanding economy required and as well the huge new layers of workers it needed, because as it steadily bankrupted the peasants and robbed them of their land, its forced them to go to the cities to become workers. The dis-accumulation of the peasants, the robbing them of their wealth, was the precondition for the continued growth of capitalist accumulation.

In a way, capitalism as whole somewhat resembles a gigantic Ponzi or pyramid scheme. Like such a Ponzi scheme, which requires every growing numbers of new investors to pay off the older ones, capitalism requires ever expanding sources of new, non-capitalist-produced wealth to expand its profits. Only as long as capitalism could expand these external markets, could it grow. But capitalism as a whole has one big difference from a Ponzi scheme, in which money is merely shifted around. Despite the immense destruction involved in imperialism, despite the destruction of whole peoples, the reduction of others to miserable poverty, capitalism could and did increase the real overall productive forces. For although capitalism bankrupted the peasants, the productivity of workers were immensely higher, so the overall amount of goods increased and as part of the increase workers’ standards of living eventually grew as well. The wealth lost by the peasants—land and what lay under it—was transmuted in the hands of capitalism to far greater wealth. Indeed, the descendants of peasants-turned workers eventually (over generations) ended up with higher living standards than their ancestors had had as peasants. But this process could not continue without limit, because eventually the whole world was enveloped in capitalist trading relations and capitalism ran out of new peasant markets. Indeed, since the process can only continue as capitalism consumes and destroys those peasant markets, capitalism destroys the conditions for its own expansion.

What happens when capitalism can no longer expand? It turns inward and starts to consume the society it has built up. When the external market ceases to expand, the entire surplus cannot be sold. To the capitalists, this appears as a crisis of over-production—goods cannot be sold for the expected profit. The response of the capitalists is to cut costs by reducing wages—trying to dis-accumulate the workers, transferring wealth from the working class to the capitalists. This of course means a contraction of the internal market, and further overproduction and a fall in prices. The capitalists cut production, to try to support prices, leading to mass unemployment, a further fall in wages and a further contraction of the market. In other words, capitalism drives itself into a Depression.

The First Great Depression

The first time that capitalism faced this crisis was right before World War I, at the very time Luxemburg described the process in her book The Accumulation of Capital, and the result was the first World War and the Great Depression. With no more new markets available what followed was a World War to re-divide the existing markets, to steal markets from other imperialist powers and force them to dis-accumulate. But the war, after ten million dead, could not and did not resolve the crisis. During the war, there was an enormous attack on living class living standards and widespread disruption of production. From 1917 to the early 1920’s, the world working class responded with a revolutionary upsurge. The Russian Revolution exacerbated the realization crisis by severing trade between the Russian peasantry and capitalist corporations and thus reducing the external market. And capitalists were forced into temporary concessions to attempt to defuse the workers movement. But the workers movements failed to take power in the West, while in the Soviet Union, power ended up in the hands of a party bureaucracy, not in those of a democratically-organized working class.

When the workers’ upsurge failed to lead to actual revolutions in Europe, capitalists were able, by 1923, to manage a temporary stabilization—the speculative bubble of the later ‘20’s, which serves as a model for the much larger bubble of the past 20 years. There were two conditions present at that time for the formation of a speculative bubble. First, the capitalists could not invest their profits fully in actual production because they had too few new markets. The money that could not be invested in factories was the key factor in fueling speculation. If you could not invest in real production, you invest in paper—stocks, and debt to finance their speculation. But the second condition is that there be some, however, limited, new markets to generate profits to inflate the bubble. In the 1920’s the only source of new markets was the redistribution of Germany’s East European markets to the United States by means of Germany’s WWI reparation payments.

As with other bubbles, this one was accompanied by the expansion of debt. The US made loans to Germany, which used the money to pay reparations to England and France, which in turn used that money to repay war-time loans back to the United States. At the same time, profits from trade with newly-opened East European markets flowed into the US stock market boom which took off in 1924. Hand-in-hand with the pouring of money into speculation was the stagnation of investment in real production, leading to unemployment levels in Europe of 10% or more during the “booming” ‘20’s.

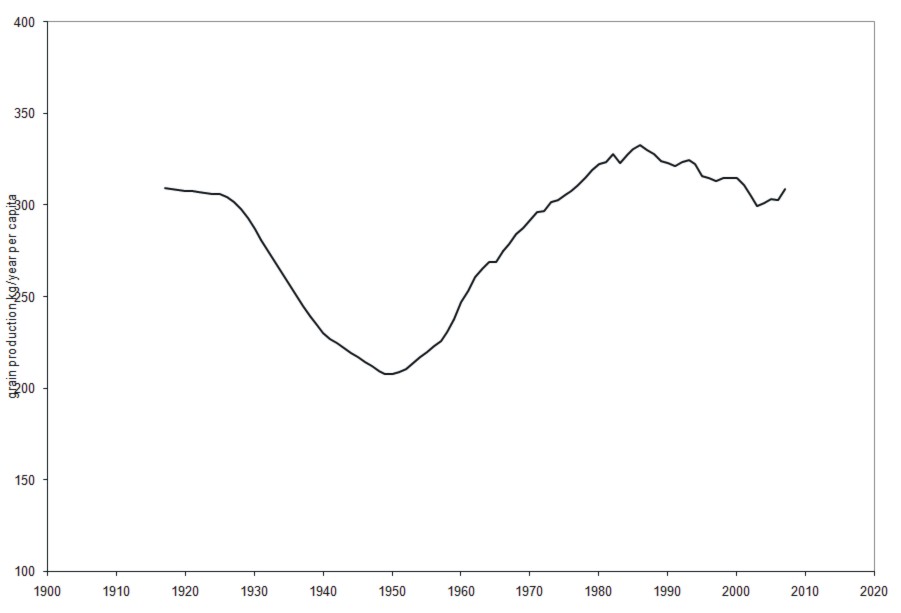

With only a re-distribution of markets available, the speculative bubble of the ‘20’s could not outlast a single business cycle—the decade-long cycle of investment and profit. No real growth resulted: by 1928 the global economy had only recovered to the same levels of per-capita steel production and per-capita grain production first achieved in 1913. With the recovery compete and surpluses returned to their pre-war level, the flow of profits that inflated the bubble dried up and the bubble popped in the crash of ’29.

The crash turned into the Depression as capitalism drove the world economy into a downwards spiral. Faced with huge losses, capitalists sought to cut costs—in other words transfer the losses to the workers. Wages were slashed and consumption dropped, leading to mass unemployment. But of course that led to a shrinking of the internal market, so that not only could the entire surplus not be sold, much of the goods essential for maintaining production at a given level could not be sold either. This led to more losses and more wage cuts. The process of dis-accumulation was turned against the working class. And since workers had no real assets or savings, such dis-accumulation could only means cutting incomes below the level needed for reproduction.

While in some regions working-class mass resistance, such as the mass strikes in the US and France in the 1934-37, stopped the erosion of wages for a time, elsewhere fascism atomized workers organizations and drove living standards ever downwards. Fascism represented as step in the devolution of capitalism into a new form of slave-labor, and in the course of World War II forced labor, rather than wage labor, became vital to the German and Japanese economies.

The end of World War II and the defeat of fascism were able to end the crisis begun in 1914. The vast destruction of productive resources and the post-war wiping out of most of non-US capital reduced the surplus produced below the size of the external markets available. By 1945, the surplus produced by the world economy and the whole scale of productions had drastically declined from 1929—food production per capita had dropped by a third, as had steel production. But that reduction of real production would not have stopped the crisis if the same amount of capital was still demanding profits to be realized. The victorious American capitalists wiped off the books nearly the entire capital of the defeated powers, and drastically devalued the capital of the weakened allies, France and Great Britain. The system of competing imperialisms was replaced by a single multinational imperialism, headquartered in the Untried States. Since the surplus to be sold and the profit to be made had contracted far below the existing external market, capitalist recovery could take place. This was true even though the Chinese Revolution had, like the Russian Revolution after WWI, withdrawn another large swath of peasants from capitalist trade relations.

But there was one additional precondition. In the immediate postwar years of 1945-48, a huge radical wave had forced concession from capitalists everywhere who feared that the defeat of fascism would be followed by socialist revolutions. For the post-war boom to take place, those wage gains had to be rolled back. The scale of production had shrunken, and if wages were allowed to rise to the true cost of reproducing labor, profit would be shrunken, even relative to the reduced scale of capital. Instead, when no revolutions actually took place, capitalists were able to launch political offensives, such as the McCarthy period in the United States , that broke worker radicalism and rolled back wages in the late 40’s and early 50’s. It was only on that foundation that the post war-boom occurred.

Will history repeat? The test of the last half-century

So, using Luxemburg’s theory, we can understand the broad outlines of the beginning and ending of the first Great Depression. But can this theory give us some idea of what is going to happen today and tomorrow? To see if it can, we need to check the theory against the economic history and data of the period since World War II, just as a doctor will check his tentative diagnosis against a set of medical tests. And in the process, we can see from more recent history how this present crisis differs from others in the past half-century.

The post-war recovery beginning in 1950 was the only period of sustained growth in working class living standards and global per-capita production during the entire past century. The external market expanded as peasant populations were reintegrated into capitalist trading relations that had been disrupted by war. While peasant dis-accumulation continued, with four million peasants forced off the land in Europe alone and far greater number in the developing countries, a sufficiently large part of the surplus was realized and reinvested in expanded production so that wage increases were possible, and overall living standards, even for peasants, rose. From 1950 to 1965 per-capita steel production, for example, doubled.

But if Luxemburg’s theory is accurate, then the post-war recovery should have ended when it ran into the same limits of realization, the same limits of the external market, that capitalists first hit in 1914. Was this true? With the statistics available since WWII, we can measure the size of the external market—the realization fund— and compare it to the amount of surplus that has to be realized or sold. Ideally we want to tally up everything that is sold to non-capitalist, non-accumulating producers— both farmers within the industrial countries and the developing countries as well sales to other non-accumulating producers. In practice it is better to tally up what is sold by this sector to capitalist enterprises, as that is the fund out of which the surplus must be bought. (See footnotes for the details of how this data was gathered.) In fact, during the post-war boom the surplus–profits—rose far faster, at 8% per year, than the size of the realization fund, which grew at less than 2% per year. By the mid-1960’s the recovery of global industry was complete with the whole capitalist workforce again re-integrated into production. In Europe full employment is achieved in 1964 for the first time since 1929, with unemployment rates following from 9-10% in 1957 to 1-3% in 1964. By this time a growing shortage of skilled labor allowed workers to increase wages back to the level needed for reproduction and for the first time since before the Depression, family size rose above two children in Europe—and much higher during the baby boom in the US.

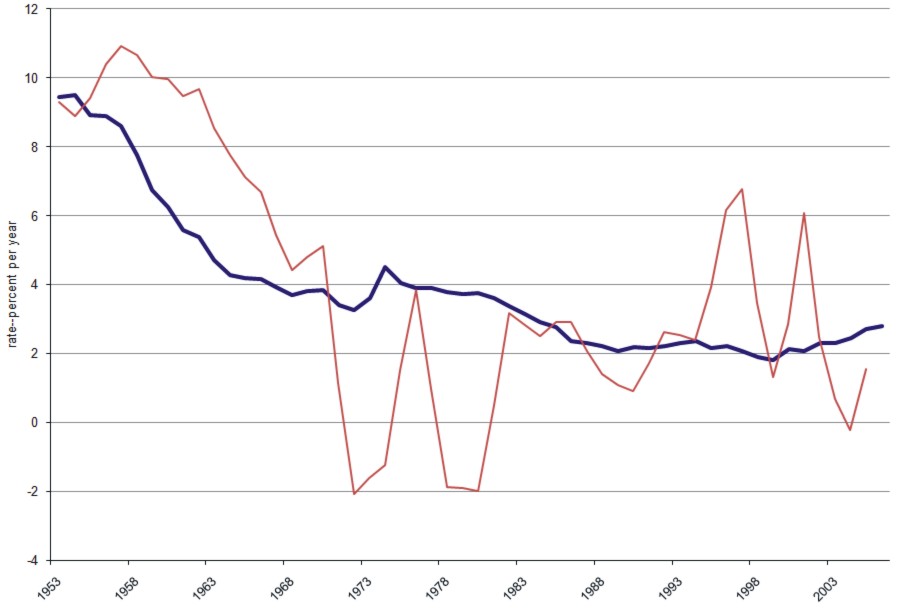

Since the surplus, and accumulated surplus—capital—was growing far faster than the realization fund, the rate of profit that could be realized started to fall drastically by the early 1960’s. If we divide this realization fund by the total amount of all capital—all stocks, bonds and loans—then we get the rate of return on capital—the profit rate that can be realized, which we can call the “rate of realization”. We can look at that figure and compare it to the actual profits that were made worldwide, also divided by total capital—the world rate of profit. (In either case we subtract out inflation.) In figure 3 we show both these figures, with the rate of profit a dark line and the rate of realization a light one. This is a kind of “fever chart“ of world capitalism and a map of the last 60 years of economic history.

What we see is that in the first decade of the post war boom, up until 1957, the realization fund was big enough and able to rise rapidly enough to absorb essentially the full 10% or so surplus that capitalist society could produce. The rate of realization and the rate of profit thus remained at about 10%. But as the realization fund grew far slower than the mass of capital, the rate of realization dropped dramatically, falling to 4% by 1964, and the actual rate of profit followed, with a lag of about five years. By the mid-1960’s all the former European colonies in Africa and elsewhere had been integrated into the US-centered global trading system. The sum of surplus seeking realization, the profit, started to exceed the realization fund. So by Luxemburg’s theory, we would expect a second crisis of realization to break out in the mid-60’s. This is exactly what occurred.

At that time, there were a series of currency crises and a rapid rise in inflation suddenly began to erode the value of capital, wiping out much of the profit. To the capitalists it appeared that costs were rising and that they could not increase prices rapidly enough to cover them, thus slashing profits. The post-war boom came to an end.

The response of capitalists to an accumulation crisis, as in 1914, was an attack on working class and peasant standards of living. Faced with falling profits, costs had to be slashed, and European governments imposed austerity policies to halt the post-war increase in wages. Wages started to fall below the rate needed to sustain working class reproduction and birth rates fell again below the two-child minimum for net reproduction. At the same time, capitalists attempted to shift production to lower-wage areas in the developing countries. But to do this, with productivity rates much lower in those countries, capital had to drastically reduce wages there too. To carry out such polices savage dictatorships were installed with CIA help in Indonesia and Brazil. The war in Vietnam was launched in large part to demonstrate that no insurgencies against such dictatorships could succeed. Everywhere, capitalism, unable to continue the post-war expansion, attempted to maintain accumulation by drastic assaults on worker and peasant living standards.

Working class resistance to the crisis

The capitalist assault collided with the steadily rising expectations that came from the post-war boom and set off a gigantic radical upsurge that exploded in 1968. From the Tet offensive in Vietnam to the French General Strike in which 10 million workers occupied factories and nearly carried out a revolution, to the global student revolts, to the mass uprisings in US cities, workers and peasants fought back. This wave of resistance continued into the early 1970’s with the Hot Fall wave of general strikes in Italy, the radical upsurge in Chile, the Portuguese revolution in 1974 and the defeat of the US invasion of Vietnam in 1975. In the face of this enormous radical uprising, which threatened to develop into a real revolution that could overturn capitalism, capitalist governments abandoned austerity and instead yielded real concessions to workers in an attempt to tame and channel the movement. Even in the direst economic circumstances, capitalists will yield concessions in order to de-mobilize potentially revolutionary movements, to retain control over the economy and to buy time for counter-attacks. Better a few years of lost profits than the loss of power!

So, in the five-year period from 1968-1973 real wages again increased globally, and in Europe other concessions were gained including much shorter working hours and free university educations. With expanded internal markets, production did not enter a downwards spiral, as in the Depression. The working class succeeded in postponing the development of the crisis for a significant length of time. But since the increase in wages could in no way solve the capitalist crisis of accumulation, that crisis was postponed, not resolved.

Just as would be anticipated from Luxemburg’s theory, capitalist accumulation ground to a complete halt in the years that followed 1968. Caught between the stagnant external markets and rising costs, profits plummeted to zero and were even on net negative for most of the seventies. The total, inflation- adjusted value of all capital was virtually no higher in 1983 than it was in 1968 as the long plateau in Figure 2 illustrates. The persistent high rates of inflation through this period were the inevitable mechanism for wiping out the profits of this whole 15 year period. Without the expansion of external markets, capitalist accumulation was impossible.

The Capitalist Counterattack

Even without net profits, so long as capital retains power over the economy it can survive. The working class upsurge of the ‘60’s and ‘70’s did not succeed in wresting control of the economy or the government away from the capitalists, did not make a revolution. So the resulting stalemate between workers and capital was inherently unstable—at some point the capitalists, retaining the levers of government and the economy, would fight to regain their profits. During the mid- and late -1970’s the deliberately planned oil price shock in 1974 and the subsequent steady rise in unemployment undermined working class momentum, and political warfare like the CIA-engineered coup in Chile and similar coups elsewhere decimated leftist ranks. Capitalists waited until the vast radicalization that had shaken world society in the late sixties and seventies had ebbed into sectarianism, weariness and apathy and then initiated a general counterattack in 1979. As was the case 15 years earlier, capitalists, confronted with an inability to expand the markets, attempted to accumulate again by cutting costs. In the process they laid the foundations for both the bubble that began in the mid-‘80’s and the present crash.

The attack began with another huge oil price shock and was followed by the rapid rise in interest rates set by the US Federal Reserve and the European central banks. These moves combined to set off a several general recession and rapid rise in unemployment. Simultaneously conservative regimes, lead by the Reagan administration in the US, launched an offensive to break the remaining power of trade unions, starting with the breaking of the air-traffic controller strike in 1981. The result was a swift fall in real wages—in the US real wages fell by 21% between 1978 and 1983. All the concessions wrested in the late 60’s by workers there were taken back. In Europe, where the workers movement was far stronger and more radical, the losses were not as great.

But in the developing countries the situation was far worse. Per-capita real gross domestic product and real wages both fell by about 40% by ’85, causing widespread privation. Driven into debt by the combination of rising oil prices and falling agricultural commodity prices developing countries fell into the grasp of the Internal Monetary Fund’s Structural Adjustment Plans which gutted health and education, drove down wages, impoverished peasants and drove them into burgeoning slums. By 1985 the offensive had transferred an enormous chunk of world income, about one-fifth, from workers and peasants to capitalists. What the capitalists failed to do in the 60’s, they succeed in doing in the ‘80’s.

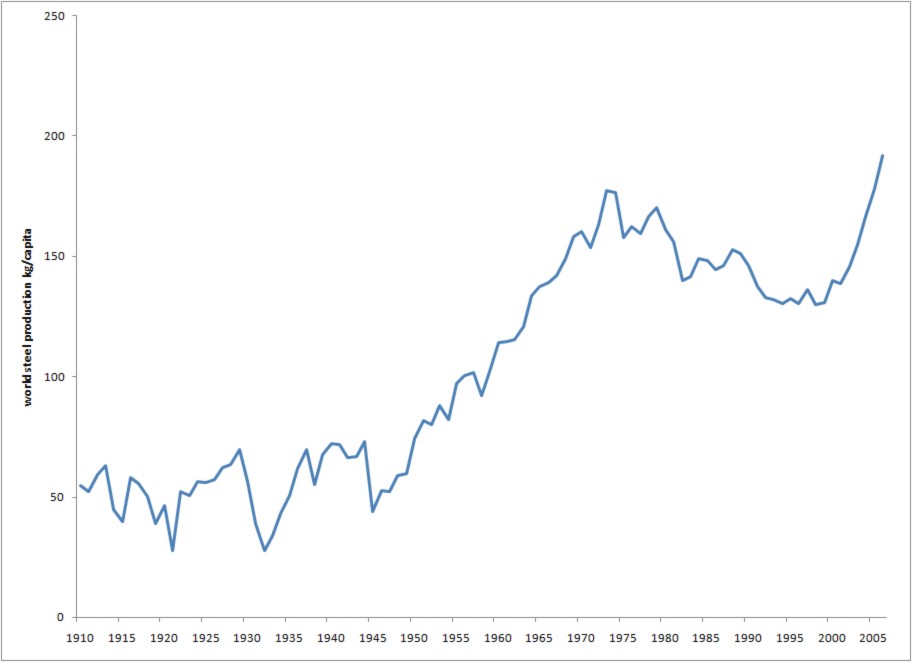

On this basis, all real growth in the economy came to an end and a long period of declines in production and standards of living began. World per capita grain production peaked in 1984 at a level only 10% above that reached in 1914, beginning a 25–year long decline that is still continuing (fig. 4). Steel per capita production peaked in 1974 and started a 20-year long decline in 1979, dropping by 28% by the end of the century (figure 5). Energy and auto production per capita followed a similar pattern, with levels in 2000 below those of a quarter century earlier.

The re-absorption of the East and the Twenty-Year Bubble

Without new external markets, new areas for accumulation, world capitalism in the late 1980’s would have entered a rapid Depression spiral of decreasing markets, slashed wages and incomes, and further decreases in markets. But instead it was able to stretch that process into a long, slow decline for twenty years—by the re-absorption into the global market of the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and China. In the process capitalism was able to re-start accumulation and create the bubble that has now burst. The new markets generated by the absorption of non-capitalist producers created the key condition that supported the bubble, and that now is no longer present.

Beginning in the late ’80s and accelerating through the recession, capital launched on a huge campaign of privatization, to convert markets formerly held by state-owned companies to markets for private capital. Like a creditor foreclosing on a factory, international creditors, holding billions in uncollectible debts, forced Third World countries to sell off state owned factories, generally for fraction of their real value, in return for debt reduction. In the industrialized nations, too, conservative governments like Thatcher in England began to sell off state owned industries like steel, again with the rationale, or excuse of using the proceeds to reduce debt. But these privatizations were small in comparison with the size of the world market, and in comparison with the much larger ones that were to follow in the “Communist” countries.

The so-called “socialist” economies were in fact anything but socialist. Socialism means the control of the economy by the working class, and given the size of that class, such control can only be exercised democratically. The regimes in the East were instead controlled by a self-selected and self-perpetuating bureaucracy that maintained power with the help of brutal repression of workers and peasants, although it ruled “in their name”.

But neither were the bureaucracy-ruled regimes capitalist. The vast state-owned industries, like capitalist ones, did employ wage-workers, but they did not accumulate capital—there had no stocks and bonds, no money, no capital that could be bought and sold. And the accumulation of capital is, after all, the whole point of capitalism. So, like the huge peasant populations in these countries, the state-owned sectors were non-capitalist, non-accumulating producers and were therefore a potential large new field for realization and accumulation—for world capitalism. A new field, for these producers were isolated for the most part from the capitalist economy. Although in 1980 their economies together were twice the size of the developing “Third World”, their trade with the industrialized countries was only one third as much.

This was no accident. The bureaucratic regimes that ran the East bloc had limited trade with the West through state trade monopolies and had blocked the type of trading arrangements that had led to dis-accumulation of peasant economies. They had protected the industrial base that they, as a managerial class, relied on for their power. To obtain access to this large potential field of accumulation the Western countries had to “open up” the East to “free trade”. This could happen in one of two ways—by the forcible overthrow of these regimes by war, or by their internal transformation, and the peaceful conversion of the bureaucrats into capitalists.

War was more than an abstract possibility. Beginning the late 1970’s, major segments of US and British ruling circles—capitalists, political, and military—started to plan for a “limited nuclear war” which would lead to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and an end to the bureaucratic regimes. Scenarios for such a war were circulated openly—one in fact became a best-selling book—and laid the basis for the massive nuclear arms build-up under Ronald Reagan. The US-backed war in Afghanistan was to be an initial weakening of Soviet armed strength. Fantastic as these plans were, with their immense risk of all-out thermonuclear catastrophe, they remained the basis for US and NATO military planning until the mid-1980’s.

But they proved unnecessary from the capitalist standpoint, for the bureaucrats in the East proved only too willing to re-integrate their countries back into the world capital economy, becoming capitalists themselves in the bargain. The bureaucrats who controlled the economy stood to gain enormously if they could transform themselves from managers of state-owned industries to the capitalist owners of those industries. Why skim a few million off an industry when you could own the industry and have billions?

Such a process of transformation in a highly repressive society could only happen over time, through factional struggles within the bureaucracy, but by 1980 there were evident signs that it was beginning. In the 1970’s East European governments started to connect themselves with the West by accepting large loans. In 1978, Den Xiaoping announced his market-oriented reforms in China. In 1985 the process accelerated greatly as Mikhail Gorbachev initiated even more sweeping market–oriented reforms in the Soviet Union, giving wider and wider powers to the factory managers. Bureaucratic factions mobilized mass support for their policies, while workers, crippled by decades of repression, were unable to organize independently for their own interests. By 1989 in East Europe and by 1991 in the Soviet Union the process was complete and mass privatizations began to convert the Soviet bloc’s industrial base into money capital. The regimes that came to power were all formed by factions within the bureaucracy, not by popular forces overthrowing the bureaucracy. The East bloc was opened to capitalist accumulation again and the bureaucrats had become fabulously rich.

The result for capitalists was the conversion of trillions of dollars of productive assets into capital. As mass privatizations swept over the Soviet bloc, the non-capitalist sector was dis-accumulated into oblivion. This led to a global resumption of capitalist accumulation and a global boom in the value of assets. It was only in 1985, once the inevitability of the Gorbachev reforms became clear, that the current bubble of speculative capital began to inflate, in anticipation of the gains to be made when the Soviets collapsed. And it was only in 1995, after the mass privatization of ex-Soviet industries that the global real rate of profit finally took off above the low levels that had prevailed since the early ‘70’s. By the end of the century, the realization fund had grown by 60% over 1985, the rate of profit had risen to 7% (see figure 3) and the accumulated mass of capital had nearly doubled (lower line fig. 2).

The consequences for the working class of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union were not so rosy. In matter of a few years, industrial production collapsed by 50%, wages dropped by far more, health services were slashed by three-quarters. In Russia and Ukraine, the death rate increased by 50% in the year following privatization and the birth rate dropped by 50%, leading to the current continuing rapid decline in population through the entire region. While former communist bureaucrats converted themselves into multibillionaires, the workers and former of the East bloc were literally dying off from the blessings of capitalism.

Yet even this new infusion of wealth was not enough to produce real economic growth like that of the post-war boom. With the massive destruction and permanent plant closings caused by instant privatization, much of the real wealth of the Soviet bloc disappeared in the process of being transferred to the capitalists. Capital had growth faster than the realization fund, so the rate of realization, the ratio of realization to capital, fell. Despite the growth of the realization fund, the rate of realization, which limited the long term rate of profit, was still only around 2%, even lower than it had been in the early 1970’s. This was far below the rate of surplus production possible in the economy.

The consequences of the continued limitation of the external market, the low rate of realization, was that capitalists could find only limited opportunities for investment in new production. So new capital generated in the absorption of the East bloc flowed into speculation, igniting the vast bubble which is just now popping. Starting in 1985, stock prices, and then real estate value exploded. While air went out of this bubble repeatedly in ’87 and ’98, as long as new capital was being accumulated, but new investment opportunities were limited, the bubble kept re-inflating. The process was the same as in the ‘20’s but on larger scale and for a longer period of time.

At the same time, with the continued gap between the expected rate of profit and the rate actually realized, capitalists continued through this period to drive down wages and living standards, as witnessed by the continued fall in per-capita grain and steel production, the disastrous fall in life expectancy in Africa, the stagnation or fall in real incomes in the advanced countries and the steady increase in working hours in the United Sates.

Since the production for working class consumption continued to contract, capitalism turned to war production, as it had in past crises. Defense production, which boomed under Reagan and fell only slightly after the end of the Cold War, allowed production to continue without any demand for real goods. It went hand-in-hand with the speculative boom in two ways. One the one hand arms production supported the prices of commodities economically by creating demand for metals and energy without increasing working class consumption. On the other, the arms were used directly in the Gulf War, and later in Iraq to materially prop up oil prices through the destruction of supply.

The Decade of China

By the end of the 90’s the absorption of the ex-Soviet Union was complete, but the absorption of China was just beginning and did not really get fully under way until China joined the World Trade Organization at the end of 2001. With a far greater population than East Europe and the Soviet Union combined, China was potentially a far bigger market as well. Equally important, the Chinese leadership, while by now a representative of the budding Chinese capitalist class, decided to move to privatize the state sector only gradually, retaining a core under state ownership. This was both to preserve control over the economy and to limit the extent of massive layoffs that could lead to working class explosions. This was a critical policy difference from the approach of the Soviet bureaucracy, whose idea was to grab everything as quickly as they could, relying on the lack of organization of the working class to protect them.

By modernizing the state sector industries with new technology from the industrialized countries, China’s government managed to greatly increase the production of the state sector industries, even as it was transferring large chunks to private control, and shifting the majority of industrial employment to capitalist enterprises. This policy allowed the Chinese economy to actually expand rapidly even as it was accumulating capital against both the state sector and the peasantry, who were driven off the land by the hundred million. It also allowed a much expanded external trade between capitalist corporations both in the industrial countries and in China itself with the state sector non-accumulating producers.

The connection between the accumulation of capital in exchange with the external market and the propping up of the speculative bubble is particularly clear during the past decade with China. Dollars earned by capitalist corporations in China (both multinationals and Chinese-owned) were converted to yuan to buy raw materials and semi-processed goods like steel from the Chinese state sector and peasants. The dollars then were recycled back to the United Sates by the Chinese government in the form of a huge flow of loan capital. This flow of loans in turn keep interest rates low and fed the speculative boom in housing prices, and the accompanying ballooning of mortgage loans. So long as the multinational could continue to profitably invest more and more capital in China, so long as the trade with the state sector could continue to expand, the bubble could be supported.

Indeed, in China itself, this cycle did lead to greatly expanded production, with growth rates in the years 2002-2007 in some sectors exceeding 20% per year. In the urban areas, real wages and living standards unquestionably advanced. Gains in Chinese production were in fact so large that for this brief period of six years, they actually reversed the long-term declines in global per capita industrial production, recovering or slightly exceeding the peaks reached back in the 1970’s(See figure 5).

So long as the trade with China’s state sector continued to increase, this cycle could continue. But as for every source of new external markets, China’s limits were soon reached. In just six years, by 2007, the output of the state sector was fully absorbed in international trade. In fact, by late that year total Chinese imports matched the combined output of the state manufacturing sector and agricultural sector. Nor could the state manufacturing sector continue to grow at the same torrid pace. While China’s government continued to invest in the state sector, the employment in the sector dropped rapidly at a 15% annual pace as more and more former state-owned plants were gobbled up by Chinese and multinational corporations.

In August, 2007, flows of capital from China (as measured by change in foreign reserves) peaked and by October had begun to decline—and with that the flow of capital into the United States slowed as well. By no coincidence, US housing prices started a rapid fall in those same months (they had been falling very slowly since June 2006) and the global stock markets peaked in October 2007. The last region of expansion of the external market had been exhausted and a new crisis had arrived.

The popping of the bubble and the present crisis

As soon as the expansion of the external market stopped propping up the bubble by funneling increasing amounts of money into US debt, the bubble began to pop. For the first year, the deflation was limited to the US real estate market. But it is in the nature of asset deflations that they tend to snowball. As assets drop in value, more people try to sell them, dropping their value further. Then, as the assets fall below the value of the loans made against them, the losses spread from the asset-holders to the creditors. Since the loans are the creditors’ assets, as they default, and drop in value, the creditors in turn are faced with holding fewer assets than debts and facing bankruptcy. Without new infusions of capitals from new external markets, this cycle tends to grow, taking in an ever-enlarging circle of debtors and creditors.

In the past year, the deflation was magnified by the use of the now-infamous derivatives. These debt-based securities are really nothing more than bets on how much of the underlying debt will be actually paid off. For a given derivative, an investor betting that 95% of the loans will pay on time might get back double his money if 98% paid, but lose everything if 92% paid. In a rising bubble the derivatives were ways to make mountains of money for relatively small investments. But in a deflation, they became vehicles to magnify the losses so that a derivative based on say, moorages, might become worthless even if 80% of the mortgages paid on time.

As the underlying mortgages started to default in greater numbers, the derivatives based on them withered in value much faster. As more and more banks and other financial institutions came to hold more man more worthless assets, their own solvency came into doubt. At a certain psychological tipping point in September, the deflation became a panic as the financial institutions and wealthy investors moved to rapidly dump the assets that now were clearly overvalued, and in fact might be utterly worthless. Finally, as institutions were forced to raise money to pay off their own creditors, they began to sell all assets, including commodities and stocks. The result was the crash of October 2008 with stocks and commodities both falling by almost 50% in a single month, comparable to the collapse of ’29.

The financial crisis affects the real economy of jobs and goods in an interlocked cycle. On the one hand, as the prices of commodities fall, goods-producing industries like steel start to slash production in an attempt to maintain prices by reducing supply. By the end of October, for example, 17 out of 29 blast furnaces in the United States had shut down, China had cut steel production by 20% and other major steel producers around the world had cut by 20-30%. Overall, steel production in the fall of 2008 was dropping twice as fast as at the worst period of the Depression in 1931. Production decreases in turns lead to layoffs, thus cutting consumption, and driving a new cycle of falls in commodity prices. At the same time, corporations of all sorts, suddenly seeing falls in consumption, in prices and massive losses in the value of their asserts, try to cut costs by layoffs and wage cuts, further cutting consumption and further driving up unemployment. And of course, as consumption spirals downwards, the value of assets evaporates as well. As assets evaporate, financial institutions hoard cash, stopping the flow of credit to both workers and corporations, further cutting demand.

From the standpoint of capital, the cut-off of an expanding external market leads to a never-ending accumulation against the working class, with more and more wealth transferred from labor to capital, but with each transfer compounding the problem of lack of realization, since not only is the surplus unsold, but now part of the production that simply reproduces the workforce goes unsold as well. The slow self-consumption of capitalism that occurred over the past 30 years is now being massively sped up, with losses taking place over months, not decades.

Does the diagnosis pass the tests?

Looking at the whole past sixty years, does Luxemburg’s theory of accumulation fit the data, does the diagnosis pass the tests? It seems that it does. What the history of the post–World War II period shows is that, as that theory predicts, no accumulation of capital occurs when the external market ceases to expand, as was the case in the period from the late 1960’s to the early 1980’s. Conversely, accumulation only resumes when new external markets are being absorbed, as in the post-war boom of 1950-1964 and during the absorption of the East bloc economies from the late 1980’s to 2007. It is at the time that external markets are fully absorbed, as when in the mid-1960’s the whole of the developing countries were re-integrated into a recovered global trading system, and when in 2007 China’s absorption was completed, that accumulation ceases.

We can also see that, over the long run, averaged over the ten-year business cycle, the rate of realization does indeed limit the rate of profit. Looking at Figure 3, the rate of profit fluctuates far more than the read of realization, but generally tracks it. Indeed if we add up the sum of after-inflation profits realized in the whole 60 year period, $58 trillion, we find it almost exactly equals the sum of the realization fund—the sum of exports from non-capitalist producers—which was $59 trillion. On average, the rate of profit does indeed equal the rate of realization from the external market, as Luxemburg stated a century ago.

Finally, we see that when the rate of realization drops below the rate that surplus can be produced, which technologically has been at least 10% per year for a long time, then capitalism seeks to drive down wages and labor income to compensate for lost profits. Thus workers income and the real economy grow only in periods, like that of the post-war boom, when the rate of realization is high, or during brief periods like 1968-73 when a radical workers movement can force concessions, at the expense of capitalist losses. But we see that, as in that period, such concessions are temporary as long as capitalists retain control of the economy.

Is there a capitalist cure?

So if the crisis is ultimately generated by the ending of the growth of the external markets, is there a capitalist way out of the crisis? Can new external markets be found? First, is there room for more growth in China? After all, the domestic market there is still small and the China’s government has the power to greatly expand the state sector. The Chinese government has announced a $600 billion infrastructure investment package, but it consists mainly of somewhat speeding up projects that were already underway. The problem is that to expand domestic consumption, rather than the export sector, will mean increasing workers income at the expense of capitalist income, increasing costs for both producers aimed at the domestic market and for exporters. Instead what the exporter industries want is a reduction of costs to compete in the shrinking global market. To obtain those reductions will mean layoffs, wage cuts, and privatization of the technological advanced state sector—in other words shrinking the domestic market and the state sector. In major Chinese cities, that is already what is starting to happen. The government is also allowing the value of the yuan to fall, competing for the shrinking world market, but making it more difficult to expand domestic consumption.

But maybe there are more China’s out there—like India for example? But India, unlike China, has long been fully integrated into the world economy, its peasants and much smaller state sector are not new external markets. The same goes for the rest of the developing world, which has long been “globalized”. What capitalism needs are new external markets to re-start growth and like a Ponzi scheme that has run out of new customers, global capitalism is fresh out of new markets. Capitalists themselves are well aware of this lack, which they bemoan in financial pages interviews—“where will the new locomotive of growth come from?” they ask.

The actual capital cure that is being tried—the massive global bailout—clearly does not even address the real disease—the lack of new external markets. The bailout is ultimately just a way to transfer wealth from workers to capital, in a very direct way. The money being so liberally doled out to the banks and other financial institutions is not of course going to generate new loans or credits, but is going almost directly into paying the dividends that these institutions no longer have the profits or assets to pay. The money to pay the bailout is being borrowed by the US and other governments. Such massive borrowing by the government, a risk-free borrower, tends to dry up lending for any other purposes, such as corporate or mortgage lending. If such borrowing is compensated by budget cuts, the result is lower consumption and another loop in the downwards spiral.

The immediate question is can the government create demand that will stop the downwards spiral of prices, production and employment? What about the tried and true alternative of armaments production? Can governments create some new threat and then support production, prices and profits with a massive arms build-up? It was after all arms production that ended the Depression in the United States at the end of the 1930’s.

The problem with arms production is that, unlike a new external market, it does not represent an increase in net demand. If an increase in the defense budget is financed by taxes on workers, demand for arms goes up, while demand for consumer goods goes down. If instead it is financed by borrowing then the same problem occurs as with the bailout—lending for all other purposes dries up.

The only way that arms production can in fact stabilize or end a crisis is when there is an immediate prospect of real external wealth. The arms buildup of the late 1980’s would have given only a very short respite from the crisis that began in the late 1960’s if it were not followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the opening up of the East bloc to trade and capitalist looting. And the far greater arms build-up of 1939-45 would have been followed by a return of the Great Depression if World War II had not wiped out the capital of other capitalist powers, eliminated huge amounts of productive resources, and opened up for US capital new fields of external realization of profit.

So, what then about war itself? Clearly, to sweep away a large part of productive resources as did World War II, we are not taking about a small affair like Iraq or Afghanistan. Even for capitalists who have not in the past been squeamish about the sacrifice of millions offline to preserve profit, arranging a world war is not so simple. For one, the capitalist corporations of the US, Europe and Japan are truly multinationals and the major capitalist economies are so closely interlinked and their military forces so merged, that a war among those counties is inconceivable. The assets of multinational corporations, their major institutional shareholders and even their boards of directors are spread across the globe. With Russia, the links to the rest of capitalism are much less close and the military forces are still independent and potentially powerful. Yet the military balance is so one-sided in favor of NATO that war is again a remote possibility.

It can’t be ruled out that if the working class achieves no alternative, a desperate future capitalist regime may launch a world war. But the development of thermonuclear weapons means that any future world war would certainly bring with it so vast destruction that the recovery would take centuries not decades, and the result would be the entire collapse of capitalism and its replacement with some more primitive social organization in a new Dark Age.

A Workers Recovery Plan — First, Transfer Wealth from Capital to Labor

Since the only capitalist options for the crisis are either a downwards spiral, or war and a total collapse of civilization, what are the workers’ alternatives? In developing such alternatives, we have to look at breaking the short-term disintegration of the economy, and at the underlying cause, just as a doctor treating a patient must first stabilize the symptoms, and then effect a cure.

The dominant process of a capitalist crisis is the continuous transfer of wealth from labor to capital, and the accompanying cycle of destruction of workers living standards and the forces of production generally. To stop and reverse that cycle is the first task of any Workers Recovery Plan. Wealth must be transferred from capital to labor.

The first and most important way to do this is through massive public works projects, financed by taxes on capitalists and corporate wealth. The aim of such programs is not merely to generate jobs but to produce the goods and services that the working class needs, at the same time employing currently idle or underemployed labor and productive resources. This does not mean the sort of highway boondoggles that pass for public works projects today, but instead real reconstruction producing millions of units of housing, schools hospitals as well as the infrastructural repairs to aging levees, bridges and roads. In every country of the world, whether industrialized or not, there is an acute shortage of adequate housing. Even in the US, housing construction has not kept up with the expansion of the population and in Europe and Japan the lack of housing is a key limitation on the birthrate and the difficulty of families to raise two children. In the US, there is an estimated shortage of 10 million units of housing and an immediate deficit of $1.5 trillion in essential infrastructure projects. In the developing countries, the shortage of housing and the adequate sanitation that goes with it reaches appalling levels, with most urban dweller living in fetid slums. Globally, there is a need for a billion or more new housing units and the water supply, waste treatment systems, schools and hospitals that go along with such a vast construction. The remediation of pollution and reforestation, and the development of new, cheap and clean sources of energy adds to the immense amount of work that needs to be done. And as with the old WPA in the US, such a public works program must mobilize the talents of millions: professional artists, scientists, engineers as well as teachers, doctors, construction and industrial workers.

Of course, such an expansion of infrastructure, including new schools and hospitals goes hand in hand with a great expansion of essential social services, first and foremost education and health. So closely tied to the demand for a vast public works program is the demand for free education at all levels and free health care.

Redirecting resources to such public works programs would have an immediate and huge impact on employment and working class incomes. In the United Sates, for example, a program of $500 billion per year would create approximately 5 million new jobs and, if similar programs were implemented in the developing sector, the demand for industrial and construction equipment would create millions more jobs in the industrialized countries.

To be effective, a public works program, must be based on direct government employment not contracting out the work to private companies. Contracting out leaves the majority of the money spent in the hands of the contractors and thus represents another form of subsidy to capitalists. Direct employment by the government means that a far greater proportion of the money ends up in workers’ wages. Similarly, the wages on these program must be the “prevailing” or union wage, not some “living wage” that is much lower.

In this way, the public works program not only creates employment, and puts money in the pockets of millions of workers, but at the same time helps to put a floor under wages generally, increasing incomes for all workers. The net effect is to break the cycle of lower production, lower wages and lower demand and to begin increasing worker living standards.

For such a program to work even over the short run, it has to be funded from capitalist wealth. Obviously funding by workers’ taxes would fail to actually transfer wealth to workers and stop the depression cycle. But deficit funding would not work either, since again it would squeeze the supply of credit. Fortunately there are plenty of source of capitalist wealth. First, the cancellation of the bailouts would save expenditures of the order of one to two trillion dollar globally. Taxation of capitalists’ individual wealth, a “wealth tax” is another large interim source. For example in the US a 2% annual tax on wealth over $2 million dollars is estimated to raise $600 billion a year. In the past 30 years, the wealthiest 1% of individual have gone from having 9% of the total income to having 23% of total income. Merely reversing that shift would raise working class incomes by 20%.

A third essential source is in the cancellation of whole categories of debt. The over two trillion international debt owed by the developing countries to the international finance system must be among the first to be abrogated—written off. In a deflationary crisis, the payment of this debt will rapidly strangle developing country economies, if workers do not act to force debt abrogation. This is an issue confronting all Latin American economies immediately. On the other hand, the elimination of some $400 billion in annual debt service will allow developing countries to begin importing the goods, especially industrial and construction machineries that they need for their own reconstruction programs, generating large increases in employment in both industrialized and developing countries. Obviously, major write-offs of mortgage and other debt in the industrialized countries is essential as well.

Finally, a critical source of both money and resources is the armaments industry and the war economy. Ending the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and halting all arms production will not only free up around $400 billion dollars per year for reconstruction. The armaments industries of the US and the other industrialized countries contain the most advanced and productive machinery in the economy. If this machinery and highly skilled workforce was converted to the production of industrial machinery, it would become an enormous source of new wealth and new employment, turning out factories instead of bombers. It again must be emphasized that the real, physical resources needed for a great expansion of the economy exist—they are just idle or misused.

In addition to a massive reconstruction program, a second major part of an immediate recovery plan is to increase wages and reduce the hours of work. In the past generation, real wages have fallen in most countries, including in the United States by around 20-25%. It is critical that this transfer of income from labor to capital be reversed, with wage increases of at least a third. Again, the result of such increases will be to allow workers to have the money necessary to raise families, to allow the working class to reproduce itself. And of course wage increases will also serve to break the cycle of decreasing demand, production and employment.

Wage increases can be demanded of the government in the form of increases in the minimum wage, but will also be won in conflicts with the employers. For this, it is vital that part of a recovery plan be the complete legalization of all migrant workers and the guarantee to them of all the rights given to citizens. Without these rights, it is extremely difficult for migrant workers to defend their wages and working conditions on the job and to join with native-born workers in demanding more. Indeed the whole point of anti-immigrant legislation has been to create a sub-class of workers forced to work for low wages, thus driving down wages for all. Legalization, and the complete abolition of restrictions on the movement of workers, allows the possibility of migrants joining, and indeed likely spearheading, a renewed struggle for higher wages.

Finally, hours of work have also increased in many countries, particularly in the United States, where hours of work have become so long that they severely interfere with family life and exhaust many workers’ capacity to do the kind of thinking and organizing that any resistance requires. Increase of hours has of course also contributed to the persistent high levels of unemployment that the crisis is rapidly compounding. Reduction of hours to a maximum level of 35 hours and prohibition of involuntary overtime will reverse that trend, and add to employment, as well as winning for workers the time they need for other battles.

A cure, not a tourniquet

These measures to transfer income from capitals to labor are essential and can break the depression cycle, but they cannot resolve the crisis. They do not address the underlying cause of the crisis, which is the end of the growth of the external market. In fact, from the capitalist standpoint they exacerbate the crisis. Wage increases add to costs as do cuts in hours, both reducing profits, while taxes on capitalists cut profits still further. As well, the growth of a huge state reconstruction sector squeezes out private producers. All this will lead to a complete halt in accumulation or even negative accumulation—net losses. This will far outweigh the expansion of the internal markets. This is exactly what happened in the early 1970’s and the mid 1930’s as radicalized workers movements obtained major concessions from capitalists in the midst of a crisis. In both cases, accumulation came to a complete halt—capitalists stopped making profits and faced losses.

Such large scale concessions to labor, at such a painful cost to capitalists, can only occur when there is a threat to capitalist control over the economy. Capitalism cans in fact survive for a while without profits and without accumulation, even with losses, just as any individual capitalist enterprise can survive such conditions—for a while. But what capitalism cannot survive is the loss of control over the economy and the government. During the ’30 and late 60’s to early 70’s period radical movements threatened just that loss of control, so concessions were granted to attempt to demobilize these movements and channel them into alliance with capitalist political parties.

But for this very reason the concessions could be only partial and in large part temporary. If a radical movement does not succeed in wresting control from the capitalists, its threat cannot last indefinitely. And when the threat is removed, capital will strike back, as it did in the late ‘30’s and late ‘70’s, taking back many (although not all) of the concessions granted earlier. In the present crisis, therefore, a recovery program that transfers wealth to labor can at best result in a standoff.

Since the cause of the crisis is the impossibility of further growth of the external market, then there is no solution of the crisis within the structure of capitalism. The crisis can only be resolved to the extent that control over the allocation of resources is no longer in the hands of the capitalists and the goal of that allocation is not the generation of profit and the accumulation of capital. Any Workers Recovery Plan that can work in the long term of more than a few years must begin to take control of the economy away from capital and put it into the hands of democratically-organized working class.

The converse of the idea that accumulation and profit requires an expanding external market is that in a fully global economy production must be carried on without profit. But if profit considerations are not to decide how productive resources are allocated, how are such decisions to be made? They cannot be entrusted to a government bureaucracy. Such a bureaucracy would ultimately become responsible either to remaining capitalist interests or, as in the Soviet Union develop into an independent layer, ultimately evolving back to a capitalist class. The essence of class society is the division between those who make the decision and those who carry them out—that is those who work. As long as there is a separate class of decision makers, society devolves back to capitalism.