Two Historical Examples of Mass Strikes

By Eric Lerner

Mass Strikes in the US in 1934

While it is uncomfortable for the business unionists who still lead the United State's unions to admit it, the present-day industrial unions emerged in the '30's out of an illegal mass strike process, led by revolutionary socialists. In the 1920's and in the first years of the Depression, the American Federation of Labor craft unions had shriveled as unemployment soared and conventional strikes became suicidal, just as similar conditions of high unemployment today, similar conservative union leaderships, has led to similar shriveling of union strength. With wages plummeting, and a quarter of the population out of work, radical opposition to business unions grew, organized in large part by workers in the Communist party, the Socialist party and in small Trotskyist organizations. These leftists sought to organize among both unemployed and unorganized layers, as well as within the shrunken unions.

Unemployed Aid Strikers

In 1933, the bottoming out of the Depression and a slight upswing in employment started to break the demoralization of the workers. At the same time, the election of Roosevelt and the promulgation of a very weak, but psychological important, protection for union organizations in Roosevelt's National Recovery Act, began to revive hopes among broad layers of workers that the deadly alliance between government and employers was cracking. But it was not until the mass strikes of 1934 that a real labor upsurge began.

On April 12, 1934, workers at the AutoLite parts plant in Toledo, Ohio struck after management refused to negotiate with their newly organized union, Federal Labor Union Local 18384. As was routine then (and is again now), the company hired scabs and strikebreakers to maintain production. But then something different happened. Unemployed workers started mass picketing in support of the strikers, rather than crossing the lines to take their jobs. The unemployed were organized by the Lucas County Unemployed League, a group dedicated to organizing the unemployed to help labor. It had been set up by members of a small Trotskyist group, the American Workers' Party, led by A.J. Muste.

Immediately the company got an injunction against the local and the League, limiting pickets to 25 per gate. The local complied, but the League served notice that it would defy the injunction. On May 21, League Leader Luis Budenz led a mass of 1,000, calling for peaceful mass picketing and smashing the injunction. The next day the crowd grew to 4,000. The following day it was 6,500, and then 10,000. On Wednesday, May 23rd, the sheriff arrested Budenz and four other picketers. Massive battles between police and ,later, the Nantional Guard, and the mass picketers followed. With the battle at a standstill, the state government, fearing a further spread of the struggle, told AutoLite that it must stop reduction for the duration of the strike, and the company agreed. After weeks of negotiations, the company gave in, recognizing the union, granting a pay raise and rehiring all strikers.

Just ten days before the battle in Toledo climaxed, on May 15, Teamster Local 574 struck the Minneapolis trucking industry. The local was led by Ray Dunne, a member of the Communist League of America, another Trotskyist organization. Every night mass rallies of from 2,000 to 20,000 were held, mobilizing not just strikers, but workers and unemployed from the whole city. Again huge battles of police and mass picketers broke out leading to a total rout of the police. The union took control of the streets of Minneapolis, even directing traffic, and panicked cops fled. It was against this background of labor news that the Toledo battle was fought two days later. A temporary truce was negotiated in Minneapolis, with the union suspending the strike and the employers reemploying the strikers. Both sides prepared for further war.

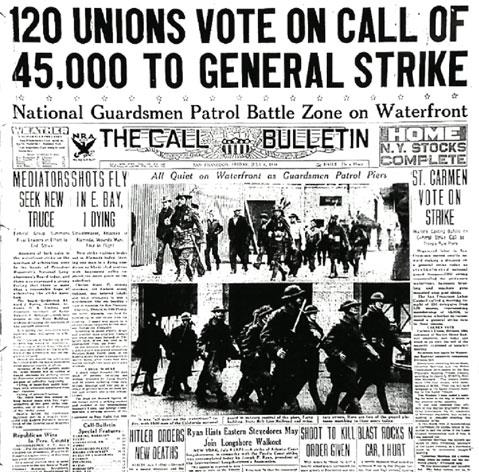

While labor battles were flaring in the mid West, the West Coast was in the grip of a longshoreman's strike -- ports from Seattle to San Diego were shut on May 8 by an International Longshoremen's Association strike for a union hiring hall and recognition. They were joined by the maritime unions. Two months into the strike, on July 5, the employers, with a newly formed trucking company, tried to break the picket lines with the help of massed police. A general battle broke out in downtown San Francisco. The picket lines were broken and the next day the port was occupied by the National Guard.

General Strike in San Francisco

In response, the Joint Maritime Strike Committee appealed for a general strike. Although the Central Labor Council declined to issue a call, individual unions began to respond. On July 9, a massive funeral march was held for the slain strikers. A huge wave of support for the Longshoremen swept the city, yet most of the union leaders urged their members not to join a general strike, which was, in any case, illegal. But at meeting after meeting workers swept aside these objections and voted to strike. Teamsters, construction workers, and dozens of other unions voted to strike, beginning July 12. Under intense pressure from the base, on July 13 the Central Labor Council voted a general strike. For four days from Monday July 16 through July 19th, San Francisco was shut tight by a general strike. On Thursday, the employers agreed to arbitrate outside differences, including the hiring hall, and reluctantly the ILA went along, ending the general strike. After several months of arbitration and further negotiation, the union won a complete victory: recognition and the union hiring hall.

The same day the general strike in San Francisco began, the teamsters in Minneapolis resumed their strike. On July 20, one day after the end of the general strike, there was another pitched battle in Minneapolis, ending with two slain strikers and seventy two injured. Again there was a mass procession of 100,000 workers. And again, the National Guard was called in, this time by Farmer-Labor Governor Olson. Guerrilla war raged in Minneapolis. Faced with the prospect of an open ended battle, and mindful of recent events in San Francisco, Olson forbade further truck shipments except for necessities. On August 21, the employers, strapped for government protection, capitulated.

In four months, American labor had won three major victories. Their tactics were defiance of injunctions, mass picketing, self-defense sq uads, organizing of the unorganized and unemployed and the general strike. It was on this basis that the previously unassailable alliance of government and employer, the strength of the National Guard, was broken. Ultimately politicians knew that further application of armed might would lead to only further spread of the conflict and further unity of labor.

The process of mass strikes

The mass strikes of '34 followed the broad pattern Luxemburg had described --small groups of radical socialist convincing workers of their common interests, the unification of organized, unorganized and unemployed workers, the successful defiance of anti-labor law, and the building of permanent organizations and the wining of concessions by the political threat of the mass strike's growing unity. In was in the wake of the 1934 mass strikes that the Federal Government, with the Wagner Act, moved to get out of the open alliance with employers in strikes. By codifying the ways in which labor could organize, the Wagner Act sought to channel the increasingly radicalized labor movement into a legal framework. Without the strike of '34, it would never have been passed. But now, fearful of the new labor upsurge, the Federal government was ready to make major concessions, making it easier to organize unions.

The French General Strike of 1968

The largest mass strike in history was the French General Strike of 1968 It was this event that signaled the complete transformation of the labor situation in the world. In 1967, the French government, under Charles DeGaulle, had taken the offensive against both workers and students. A series of ordinances were passed which would cut back unemployment compensation, gut social security benefits, restrict union rights and activities and massively contract the public university system, which at that time did not come near providing enough places for all those qualified. Throughout early '68, worker and student agitation against the ordinances and the Fouchet educational "reforms" increased. In the case of the students, the protests were spearheaded by small Trotskyist and anarchist organizations, as well as by the far broader Union of Students, the UNEF.

Repression is met with spreading strikes

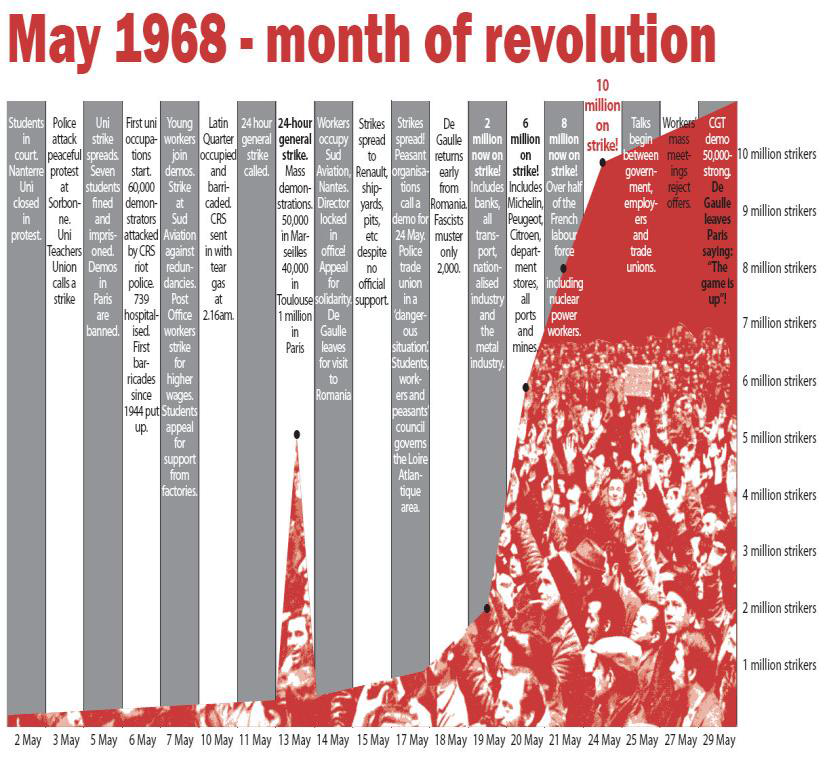

The government, intent on implementing the reforms, met the protest with repression, repeatedly calling in the police and the detested National Guard, the CRS, to disperse student demonstrations. In late March, the entire campus of Nanterre University had been closed by the government following student protests. Student leaders went to the Sorbonne in Paris to gather support. In May 3, several Trotskyist groups organized a protest against the repression in Nantern at Sorbonne. The administration called police onto the campus, leading to a pitched battle with 600 students arrested and hundreds more injured. Within three weeks the movement sparked by this incident would engulf the entire nation in a general strike. Such is the speed of mass strikes in modern conditions. To protest the attack on Sorbonne, the UNEF called for a student strike and a demonstration in Paris on May 6. Twenty thousand students turned out, only to be attacked by the CRS. This time students responded by erecting street barricades. Despite the resistance of the French Communist Party which labeled the students "insignificant groupuscles" and attempted to prevent worker support, the movement began to grow, and the UNEF appealed openly for broad labor support. Workers and leaders near the base responded, seeing the links between the student battle against the reformers and their battles against the ordinance. Such links were strengthened by leaflets from the Trotskyist groups.

In the following weeks, there were a growing series of demonstrations and clashes with the police, climaxing in a bloody attack by the police on May 12. On May 13th, under intense pressure from rank and file workers, the communist led CGT, joined by the two other labor federations, called a one day general strike of protest against the repression and a demonstration in Paris. The response was overwhelming -- one million workers, students and others paraded in Paris, the largest demonstration ever there. Under the protection of this massive demonstration, students occupied Sorbonne. The following day, workers at the big Sud Aviation aircraft plant in Nantes, went on strike, occupying their factory. But now the demands were no longer merely defensive, protesting the repression. Now they were to overturn the ordinances, revoking the Fouchet plan for the universities, to reduce the workweek from 48 to 40 hours with no reduction in pay, a massive increase in the minimum wage to 1,000 F per month, increases in vacation, a reduction in the retirement age. The working class had passed to the offensive.

Now the strike advanced with giant strides. First in aerospace and metalworking, and then in all industry, plant after plant went on strike and was occupied by the workers, bedecked with red banners. Within four days of Sud Aviation's first action, one million workers were on strike, occupying their plants. Within six days, there were seven million strikers, within eight days, 10 million strikers. The strike was total in manufacturing, but it spread well beyond -- the schools were shut, the trains had stopped, Paris was paralyzed as the subways and busses and cabs ceased to operate, shops and department stores closed, all but the most essential services stopped.

Throughout France, workers took over their places of work; everywhere there were red banners, and the echoing strains of the International. To the economic demands were now added political demands -- DeGaulle Resign, Popular Government, Workers Power. In many of the plants, the workers began to expect that the strike would lead to a peaceful socialist revolution, that the plants they occupied would soon belong to the working class.

The next week, with the general strike full, with more than half the total French working force on strike, with the peasants supporting the strikers, the fate of France hung in the balance. The most critical question was who was running the general strike? The strike had emerged from below, not on the call of the Communist and Socialist leaders of the main union federations. But only the federations were organized on a national scale, so as the strike grew, they immediately assumed the right to negotiate with the government on behalf of the strikers. Yet the federation leaders, Communists as well as Socialists, were not in the least interested in either a socialist revolution nor even in pressing the government very hard. The PCF in France, as elsewhere, had long since assumed the role of the old social democracy, supporting socialism in rhetoric, while dealing "in a business like way" with capital, and defended in practice capitalist rule and policies.

For the workers to gain control at the national level of their own strikes, they needed to form a national strike committee. Throughout France elected strike committees sprang up on the factory level, and even in some areas on a city wide level, similar to the Soviets of the early Russian Revolution. Left groups and union militants gathered during the growth of the strike and while it was at its peak, for the formation of a National Strike Committee, which could in truth speak for the strikers. But these efforts were not successful. At root the cause was, on the one hand, the extreme weakness of the leftists, mainly Trotskyist organizations, which numbered in the hundreds, and on the other the residual trust most workers still had in the union leadership, a trust rooted in the gains of the post war period and in the lingering prestige the Communists had from the days of the resistance.

But the CGT and the other Federation leaders were about to massively betray that trust. On May 27, they reached a tentative agreement with the French government to end the strike. The government granted some concessions -- a 600 Franc per month minimum wage, a general wage increase of 10%, to both state and private workers. But the key issues of the strike, the ordinance of the Fouchet plant, the decrease in hours, all went unresolved, to say nothing of the political demands for DeGaulle's resignation. The general agreements were greeted with mass opposition by workers, but it was not unified on a national scale, and the CGT leaders worked to isolate the strikers, cutting off plants from each other. At this critical point, with the strike wavering between its base and the Federation head, DeGaulle took the offensive, announcing on May 30 that the key issues, which he defined as "participation by workers" a form of worker management cooperation, would be decided by a referendum. But far more ominously, the same day paratroop divisions were reported to be moving towards Paris. The threat of civil war hung over France.

This was the critical junction for the General strike. To move forward, the strike would have to create its own leadership at a national level, repudiate the General accords and prepare to defend itself against the paratroopers. With the strike entering a second week, the strikers would have to begin to take control of essential services, themselves organizing the provisions of food and other necessities as did, in fact, begin to happen in some cities. But in the face of the opposition of both the government and the Union Federation leaders, this task proved impossible. The union leaders went from plant to plant arguing that each one was isolated, urging a return to work. In the end, plant after plant voted to resume work and within a week, the general strike was ended.

While the strike did not win most of its principle demands, and merely shook but didn't shatter capitalist rule in France, it represented a huge victory for the entire world working class. It won substantial concessions immediately, so the workers self confidence was strengthened, and it demonstrated that the mass unity of the working class was possible in the present day, not only in the past. The force of the strike, the threat of a revolution, frightened capitalists not only in France, but globally. In France, employers and government alike staged a long retreat dealing out repeated concessions to avoid a repeat of May '68. In the following five years, in response to repeated strikes, French hours of work did indeed fall, dropping by about 2 hours a week, and a further two hours by 1977. Real wages rose sharply, increasing by nearly a third from 1967 to 1973. The ordinances and the Fouchet plan were in fact quietly scrapped not long after the strike. Indeed, to quell student unrest, the university system was substantially expanded, eliminating, to a large degree, the two-tiered educational system of France.

- Log in to post comments